The Biggest Mistake in Digital Products

A Validation Story

“That’s one of the best ideas I’ve ever heard.”

My cofounders and I heard different variations of that phrase all the time when telling people about what we were building. Our pitch was met with almost exclusively encouraging, validating responses.

We had built a small alpha test app to gather data to support the pitch and had 25 or so active users from our friends and family.

With data in hand from real people in our target market, we strengthened our pitch and quickly closed a million dollar seed round1. Seven figures worth of "validation", and we were going to put it to work.

We turned the alpha test off - it was labor intensive and didn’t scale. We hired a team of people and went heads down to build out as much of our expansive vision as we could ahead of launch.

Even with the founders taking way below market salaries, our growing "burn rate" gave us about a year - there was no time to lose.

Months later2, we launched. People signed up and used the app, but it was not the overwhelming flood we expected.

I was so confused. People kept telling us it was such a good idea! Why wasn't there a flood of users signing up and coming back?

The Mistake

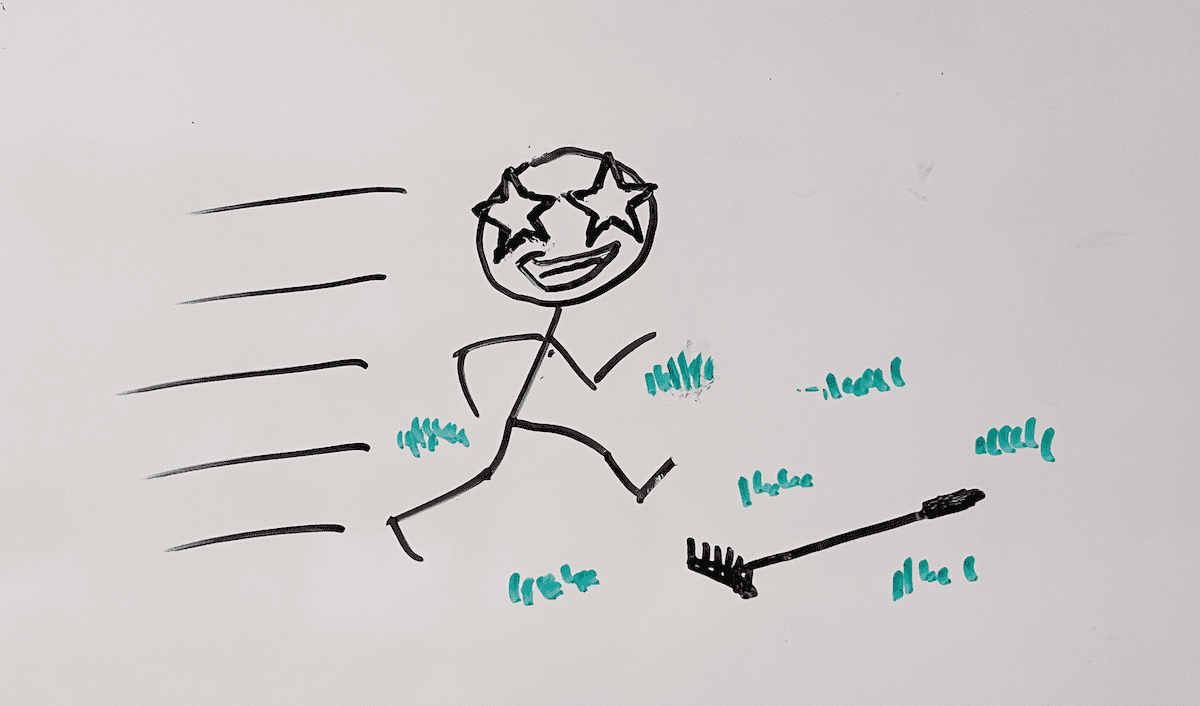

The biggest mistake in digital product development is believing the specific thing you’re building is "validated" when it's not.

That’s not to say that the vision you have won't succeed if you can make it a reality. It might even be transformational.

But, building a sufficiently valuable subset of your vision is harder and will probably take much longer than you think.

I’ve seen this mistake play out directly many times in my career now. I hear about it from friends, and can now even spot the symptoms pretty quickly from the outside looking in. It happens at startups, big public companies, and everywhere in between.

I really feel for everyone grinding away and doing their best trying to make a big bet pay off. It does work, the odds are just very small.

Words to be Wary of

So many forces are pushing energy away from ongoing discovery and toward focusing on just building until things are “ready.”

The assumption that leadership knows exactly what to build is hard to dislodge, especially when leaders believe it.

Here are some common phrases that should set off alarm bells:

- “Our customers are telling us what they want. We just have to go build it!”

- Potential customer: “That sounds really great. Let me know when it’s ready and I’ll take a look.”

- “I just met with (dream prospect) and they said if we build (feature x,y,z), they’ll sign!”

None of these things are bad in and of themselves. The mistake is when they lead you to stop the ongoing process that uncovers the specifics that can make those statements true.

You need some amount of luck to get the details right no matter what. To make more of your own luck, the right details have to be discovered alongside customers and users.

What people do is worth so much more than what they say. It’s important to get in position to observe what they actually do as early and often as you can.

How Not to be Fooled

It’s really hard to keep your head on straight through this process. Here are the things that I’ve found to be most helpful:

Budget Smarter

Whether you’re putting together an annual operating plan, a product roadmap or deciding how you choose to allocate your "sweat equity", it’s all budgeting.

Assume you’ll need more time, effort, and money than what it will take to build the first version of something before you’ll see good results. You’ll probably need a good deal more.

Given that, how does it change your approach?

Instead of just planning out features to build, think in terms of the specific, measurable goal you’re trying to accomplish with each feature. This will give you and your team room to find multiple possible paths to that goal. Do your best not to focus on more than one goal at a time.

Get something interactive in front of your target market as soon as you can. Do it even if it’s just to a small private group, and even if it’s all just people behind the scenes and not scalable technology.

The most important thing is learning whether it’s useful or at least promising to your target customer. If you can’t get people who aren't already your biggest fans to care or engage regularly, you’re in the danger zone.

If you’re building something new on top of a product that’s already viable, do everything you can to avoid committing to build unrelated features after what’s in progress is slated to be done. Especially when you really need what’s in progress to work.

Talk to target customers the right way

It’s not too controversial to say you should have conversations with customers and potential customers regularly.3

The challenge is that having the wrong kinds of conversations can give you what feels like validation but isn’t. There are great ways to do ongoing research that aren’t heavyweight or crazy expensive.

The Mom test is a short book4 and should be required reading for any founder or practitioner in this business.

More formal switch interviews and continuous discovery practices are more effort to learn, but can pay big dividends.

Whatever you do, don’t avoid including key team members from all disciplines when having and especially digesting the customer conversations you have.

Including members from design, development, etc. often uncovers many more insights vs. trying to translate your own takeaways into “requirements”. Without that, a ton of important context gets lost for the people crafting the actual solutions.

Measure Leading Indicators

It’s easy to figure out whether you’re making the revenue and the margins you need to hit growth and profitability targets.

The problem with the financial metrics is that they happen as the result of work that was done in the past. Maybe a long time in the past.

What can you measure to help you know whether you’re on the right track right now?

Most often, “leading” indicators of success won’t be obvious at first. Finding a product's north star is not as easy as looking at the sky for the brightest light. Take your first best guesses, make sure you can measure and report on them, then review. Including team members is also crucial here.

Plan for the time to update measurements as you learn more over time and find where the correlations are. Being able to measure success indicators should be as core to your product development process as testing that a new feature is working.

Again, what your target customers do is a much more important validation signal than what they say they will do.

How can you build in such a way that you can measure actions and not words sooner?

Burn Baby Burn

Back to 2015.

After some weeks of scrambling post launch, we did get back to doing things that didn’t scale and found many ways to shorten our feedback loop. We did some really clever experiments I’m proud of and got some great insights from customer interviews.

But, it was too late. We had burned too much money and couldn’t recover enough momentum before we just ran out of cash.

“It'll happen to yoooou”

You might think it was obvious we were making a dumb move in trying to build so much of our vision before launching. We were convinced we had to have at least a little bit of every piece in place for it to be valuable to customers.

In my experience, it’s by far the most common approach people take when building something new and ambitious5.

Again, sometimes it works! Just not near as often as it’s tried.

Odds are, most people who do this work will have to learn the lesson the hard way along with me. Maybe more than once.

Find ways to feed your optimism without believing too much of your own hype. Never stop investing in effective discovery and testing out insights ASAP. It’s simple, but not easy.

Good luck!

Building something ambitious and want my help increasing your odds of success and avoiding this and other mistakes? Let's chat.

-

At the time in 2014, this was a relatively large seed round, especially for a company based in the midwest.

↩ -

SIX months later to be specific. 🤦♂️

↩ -

Don't get me started on faster horses.

↩ -

The Mom Test is also the best and most natural audiobook in the genre I’ve ever listened to, if you like reading by listening.

↩ -

See also: rebuilding something that works but has limitations with new, better tech. This scenario is probably the source of the second biggest mistake in digital products. It has similar symptoms and usually costs way more than people expect.

↩

Join My Mailing List

- New Posts in your inbox.

- Interesting things I want to share.

- Not too frequent.